My friend James Bollen’s latest book, Wallpaper, The Shanghai Collection (2015), is visual meditation on the aesthetics of absence. Inspired in part by seeing an exhibition – Aestheticism: The Cult of Beauty, 1860-1900 – at the V&A Museum in London in 2011, and by the ruined buildings he encountered in Shanghai when working on his previous book, Jim’s Terrible City: J. G. Ballard and Shanghai (2014), Bollen reflects on the disappearing shikumen districts of China’s most international and forward looking city.

Nowadays people outside China are probably most familiar with the riverside skyline of Shanghai’s Pudong area, an ultra-modern forest of gleaming skyscrapers – the heart of big business and banking in modern mainland China; but some might be aware of the Bund on the opposite bank of the Huangpu river, equally renowned throughout the globe as glitzy and modern in its own day at the start of the last century. And some may even be familiar with the phenomenon of ‘nail houses’, which have provided some iconic images of resistance to this fast paced rush towards urban renewal. Such houses are a contentious political issue in China, where the land is state-owned and tenants who dispute the official offers of re-housing and compensation put to them often face acts of unofficial coercion designed to compel them to leave.

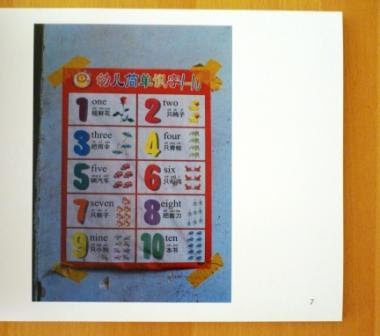

Smashed roofs and windows, power supplies cut and piped water turned off are just some of the tactics used in attempts to make such houses uninhabitable. Once the tenants are gone, both those buildings vacated without fuss and those eventually vacated by pressure, are striped bare of every salvageable and saleable commodity. All that remains usually are the memories of their former inhabitants etched upon the very fabric of those walls; the former homes which have witnessed generations being born, growing up, and growing old beneath those sheltering roofs. Often several families at a time during the Mao era crammed themselves into tiny rooms within a single home, with rows of such tenements forming tight knit communities without much space for privacy. All that’s left is often only the wallpaper.

“Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.”

These are the words of William Morris, from his Hopes and Fears for Art (1882). Morris and his ideas about art and profit form the keystone of Bollen’s project in this book. Inspired by Morris’s own work, a pattern book from the V&A’s collection and closely mirroring its Golden Type typeface, Bollen’s Wallpaper is a series of photographs punctuated with quotes taken from Morris, these excerpts become the headings under which Bollen’s images are grouped; they form the themes that explore these deserted shells, leaving us staring at the haunted qualities caught within a moment’s shutter-click. But it’s these haunted elements that speak most clearly of the human. These images capture the transience; they speak of lives laid bare. The disowned decorations of lives which have chosen to move away or been forced to move on, unknown lives which once were here but have now passed on

“History (so called) has remembered the kings and warriors, because they destroyed; Art has remembered the people, because they created.”

Find out more:

Read an interview with James H. Bollen about Wallpaper, The Shanghai Collection by Anne Witchard in the L.A. Review of Books

Further Reading:

Read my review of Shanghai Homes: Palimpsests of Private Life, by Jie Li (Columbia, 2015) for the LSE Review of Books